Introduction: From Social Sciences to Acehnology

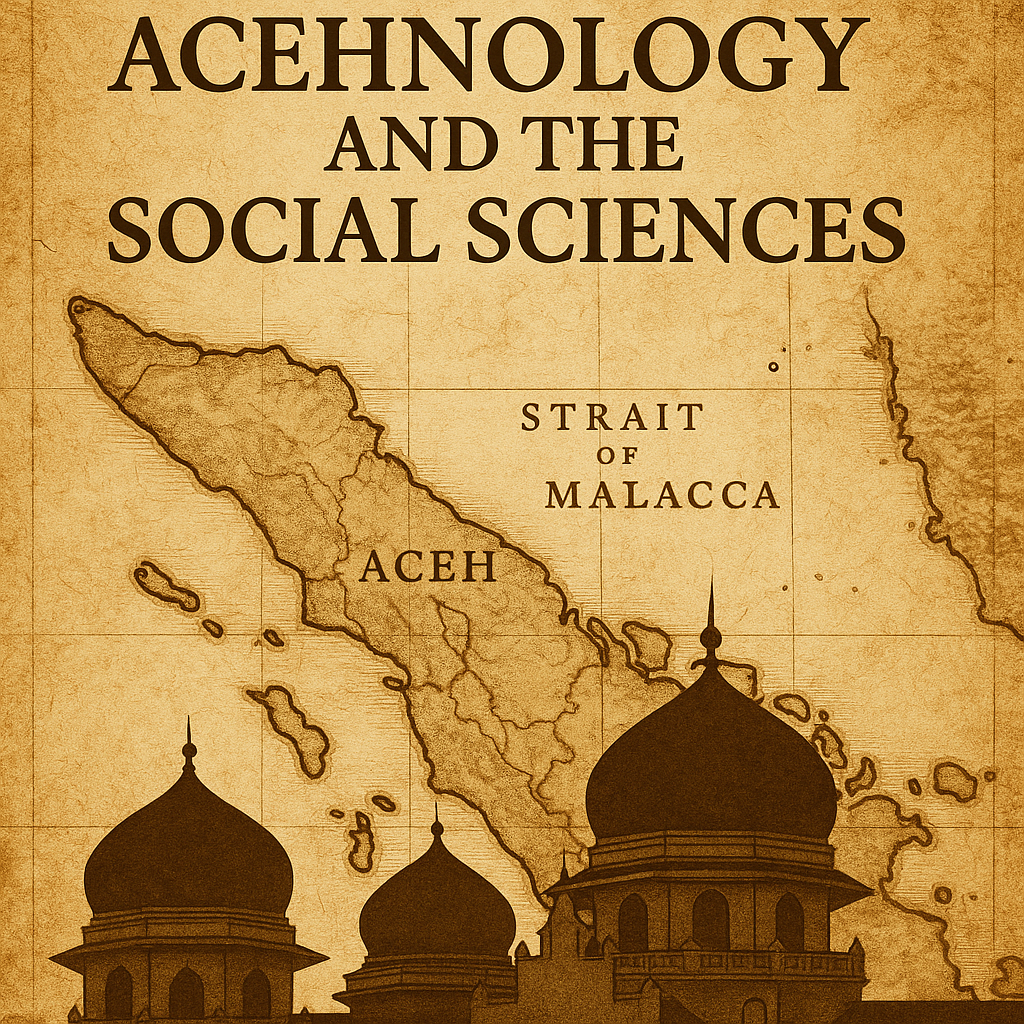

The social sciences have historically emerged from human attempts to interpret everyday life, transforming social and cultural phenomena into systematic knowledge. Disciplines such as sociology and anthropology developed because reality demanded a structured explanation. These sciences did not appear in isolation; they were born from the complex interaction between scholars and their objects of study. In this same spirit, Aceh studies—or what we may now call Acehnology—must be situated within the genealogy of knowledge production in the humanities and social sciences.

The central argument is that Aceh should not be relegated to the margins of Indonesian or Southeast Asian studies. Instead, Aceh deserves recognition as a legitimate field of inquiry, with its own epistemological foundations and scientific legitimacy. This effort requires a narrative that integrates the study of Aceh into broader discussions of area studies, ethnic studies, and nation-state studies. Only then can Acehnology claim its rightful place within the family of social sciences.

Historically, every science begins by grounding itself in observable realities. Sociology emerged in nineteenth-century Europe as intellectuals sought to explain social transformations brought about by industrialization and revolution. Anthropology emerged through fieldwork in distant societies, producing data that shaped new understandings of humanity. In both cases, lived experience provided the raw material that scholars later organized into theory. Acehnology must follow this same trajectory, grounding itself in the lived realities of Acehnese society while offering theoretical contributions beyond Aceh itself.

This means moving beyond narrow historical or political frameworks. While Aceh’s history of war and resistance is undeniably important, the study of Aceh must also embrace its rich intellectual traditions, philosophical legacies, linguistic structures, and cultural landscapes. To do otherwise risks reducing Aceh to a mere site of conflict rather than recognizing it as a contributor to the intellectual and cultural heritage of Southeast Asia.

Thus, the project of Acehnology is both epistemological and political. It seeks to challenge the dominance of Java-centric and colonial-centered scholarship, while also offering new frameworks for understanding the diversity of Indonesian and Southeast Asian life. At the same time, it reclaims Aceh’s historical role as a gateway of ideas, trade, and spirituality across the Indian Ocean.

Anthropology, Sociology, and the Foundations of Area Studies

Anthropology emerged because researchers ventured into different regions of the world to study societies that were unfamiliar to the European mind. Through ethnography, anthropologists produced knowledge that redefined the concept of “humanity.” Sociology, meanwhile, arose in Europe out of an urgent need to understand modernity. German and French thinkers in the nineteenth century, including Auguste Comte and Émile Durkheim, tried to explain the rapid social changes brought by urbanization, secularization, and industrialization. These two disciplines, though distinct, both highlight that the social sciences are rooted in context.

Philosophy and mysticism also begin from lived experience. Theories of logic, ethics, or metaphysics are not detached abstractions but arise from the encounter between subject and object, thinker and reality. This means that every discipline—even the most theoretical—is inescapably tied to the historical and cultural circumstances of its emergence. In the same way, the study of Aceh must recognize its grounding in the realities of Acehnese history, culture, and intellectual tradition.

One crucial development in the social sciences has been the rise of area studies. Unlike universalizing theories, area studies situate knowledge in geography, region, and culture. Orientalism and Occidentalism were early forms of this approach, dividing the world into East and West. Later, more nuanced forms emerged, such as Southeast Asian Studies, which recognize the region as a distinct field of inquiry. These developments highlight that geography and cardinal directions are not mere descriptors but epistemological categories shaping how knowledge is produced.

Southeast Asian Sociology and Southeast Asian Anthropology exemplify this regional approach. Both fields are grounded in ethnographic research and historical analysis specific to the region, producing theories that speak to the particularities of Southeast Asian life. This recognition of the region as a coherent field has made it possible to study phenomena such as Islamization, trade networks, and ethnic diversity in ways that transcend national boundaries. Aceh, as a central node in these processes, must therefore be included in such discussions.

In this sense, Acehnology is not a parochial or local study. It is a regional and even global project, linking Aceh to Southeast Asia, the Indian Ocean world, and broader debates in the social sciences. Just as sociology and anthropology grew from particular contexts but later made universal contributions, Acehnology has the potential to enrich wider intellectual discourses while remaining rooted in its own specificities.

From Area Studies to Ethnic and National Studies

As area studies matured, they increasingly focused on dominant ethnic groups within regions. In Southeast Asia, Chinese Studies, Indian Studies, and Malay Studies became central fields. Each of these examined not only the historical presence of these groups but also their cosmologies, institutions, and contributions to the region’s identity. This shift from regional analysis to ethnic-centered scholarship illustrates how knowledge adapts to the realities of social dominance.

Chinese Studies in Southeast Asia, for example, examine migration histories, diasporic networks, and the endurance of cultural traditions. Indian Studies focus on the role of South Asian communities in trade, religion, and cultural hybridity. Malay Studies, meanwhile, seek to uncover the roots of Malay civilization and its role as a cultural anchor in the region. Together, these fields form an interconnected web of scholarship that highlights the diversity of Southeast Asia.

Interestingly, Western influence in Southeast Asia is rarely framed as “Western Studies.” Instead, it is examined through the lens of colonialism. This is because “the West” is too diffuse as a category, spanning Europe and North America. By contrast, colonialism provides a more precise framework for understanding how Western ideas and institutions—such as democracy, secularism, and the nation-state—were imposed upon or negotiated by Southeast Asian societies.

This framework of colonialism also produced postcolonial critiques, examining how Southeast Asian societies adapted, resisted, or transformed imported concepts. In this sense, Aceh’s long history of resistance to colonial and postcolonial powers situates it as a crucial site for examining these dynamics. Yet, ironically, Aceh has been overshadowed in the broader narratives of ethnic and national studies.

As ethnic studies shifted to national studies, scholars began to focus on Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, and Singapore as distinct units of analysis. These studies often replicated dominant-majority perspectives: Java in Indonesia, Malays in Malaysia, Thais in Thailand, and Chinese in Singapore. Minority groups, meanwhile, were often relegated to the periphery, studied primarily as cases of resistance or marginality.

Aceh on the Margins of Nation-State Studies

Within this framework, Aceh has been consistently marginalized. In national studies, Aceh is often reduced to a footnote or a chapter within broader narratives. While its importance is recognized in pre-colonial and colonial histories—particularly in relation to trade, Islamization, and resistance—it rarely occupies the center stage in post-independence scholarship. Instead, it is framed as a “region” of Indonesia or as a nostalgic reference in Malaysian historiography.

This marginalization is not merely academic but political. The transformation of Aceh from a nanggroe (state) to a “region” has diminished its perceived significance in the social sciences. Indonesian studies have long been dominated by Java, giving rise to Javanology as a formal field. Malaysia, in its search for historical legitimacy, often turns to Sumatra but rarely treats Aceh as an equal counterpart. Aceh’s contributions are acknowledged but not elevated to the status of a central field of study.

Yet history shows that Aceh cannot be sidelined without impoverishing our understanding of Southeast Asia. No comprehensive history of the Malay world or the Nusantara can be written without including Aceh. Its role in trade networks, Islamic scholarship, and anti-colonial resistance is too central to ignore. The challenge, therefore, is not whether Aceh matters, but how to position its study in a way that reflects its true significance.

Unfortunately, postcolonial Aceh studies have often been framed narrowly in terms of resistance to the Indonesian central government. While this is undoubtedly part of Aceh’s story, it has overshadowed other dimensions of its intellectual and cultural life. Scholars such as Anthony Reid and Denys Lombard focused primarily on Aceh’s pre-modern history, while others like Ibrahim Alfian and Nazaruddin Sjamsuddin emphasized war and conflict. The cumulative effect has been to cement an image of Aceh as primarily a site of resistance.

This reductionist framing obscures the richness of Aceh’s philosophical, mystical, and cultural traditions. While war and politics are important, they do not exhaust the meaning of Aceh. A more balanced approach must recover other aspects of Acehnese life that have been marginalized in scholarship, including Sufism, language, literature, and everyday culture. This is precisely the task that Acehnology must undertake.

Reviving Acehnese Intellectual and Cultural Traditions

One of the most pressing challenges for Acehnology is to recover the intellectual and cultural dimensions of Acehnese life that have been overshadowed by war-centered narratives. Historically, Aceh was home to profound philosophical and mystical traditions, embodied by figures such as Sheikh Hamzah Fansuri and Sheikh Nurdin ar-Raniry. These scholars produced some of the most comprehensive works on Southeast Asian Sufism, shaping Islamic thought across the region.

Ahmad Daudy’s studies of Nurdin ar-Raniry testify to the depth of Acehnese philosophy. Even today, Ar-Raniry’s works are still read in rural communities, suggesting a living continuity of intellectual heritage. Yet younger generations often remain unaware of these traditions, as their education is dominated by narratives of war and political struggle. Reviving Aceh’s philosophical legacy is therefore essential to rebalancing the discourse on Aceh.

The dominance of war studies has also obscured Aceh’s cultural richness. Literature, language, and oral traditions are often sidelined, even though they provide crucial insights into Acehnese identity. Works on Acehnese mysticism and cosmology, such as those studied by Syed Naquib al-Attas, also demonstrate the broader contributions of Aceh to Islamic philosophy. These dimensions must be brought back into the mainstream of scholarship.

Acehnology, in this sense, is not about denying the reality of conflict but about complementing it with other dimensions of study. It insists that Aceh’s contributions to philosophy, mysticism, and literature are just as important as its contributions to resistance and politics. This multi-dimensional approach reflects the complexity of Acehnese society and prevents its reduction to a single narrative.

Ultimately, reviving Aceh’s intellectual traditions is not only an academic task but also a cultural one. It involves engaging with living communities, preserving oral traditions, and ensuring that younger generations inherit a balanced understanding of their heritage. Acehnology thus becomes both a scholarly field and a cultural movement, linking past legacies with future possibilities.

Conclusion: Toward a Multidisciplinary Acehnology

To study Aceh properly requires a multidisciplinary approach. Anthropology, sociology, history, philosophy, linguistics, and religious studies must all converge to produce a comprehensive picture. The topography, cultural landscape, and linguistic structures of Aceh are important starting points, but they must be integrated with broader historical and intellectual contexts. Only through such a holistic approach can Acehnology claim legitimacy as a scientific field.

Studying Aceh is not straightforward. Unlike Java, which has a relatively continuous identity across regions such as Yogyakarta and Surakarta, Aceh is marked by layers of historical contact, cultural diversity, and geographical uniqueness. Situated at the doorway to the Straits of Malacca, Aceh has been a crossroads of trade, migration, and spiritual exchange for centuries. This makes it both challenging and rewarding as a field of study.

Acehnology’s task is to capture this complexity. It must acknowledge Aceh’s role in global trade and Islamic scholarship, while also highlighting its philosophical and mystical traditions. It must examine resistance and politics, but not at the expense of literature, language, and everyday life. In short, Acehnology must re-center Aceh as a multidimensional subject worthy of sustained scholarly attention.

In doing so, Acehnology contributes not only to the understanding of Aceh itself but also to broader debates in the social sciences. Just as sociology and anthropology began in specific contexts but later shaped universal theory, Acehnology can enrich global discourses by bringing new perspectives from the periphery. Its insights into resistance, mysticism, cultural hybridity, and intellectual traditions can speak to issues far beyond Aceh.

Thus, the study of Aceh is not a local curiosity but a scientific necessity. By reclaiming its rightful place in the social sciences, Acehnology ensures that Aceh is recognized not only as a site of history and struggle but also as a source of wisdom, philosophy, and cultural richness. In this way, the project of Acehnology becomes both a scholarly and a cultural act, restoring balance to the way Aceh is understood and remembered.