Introduction

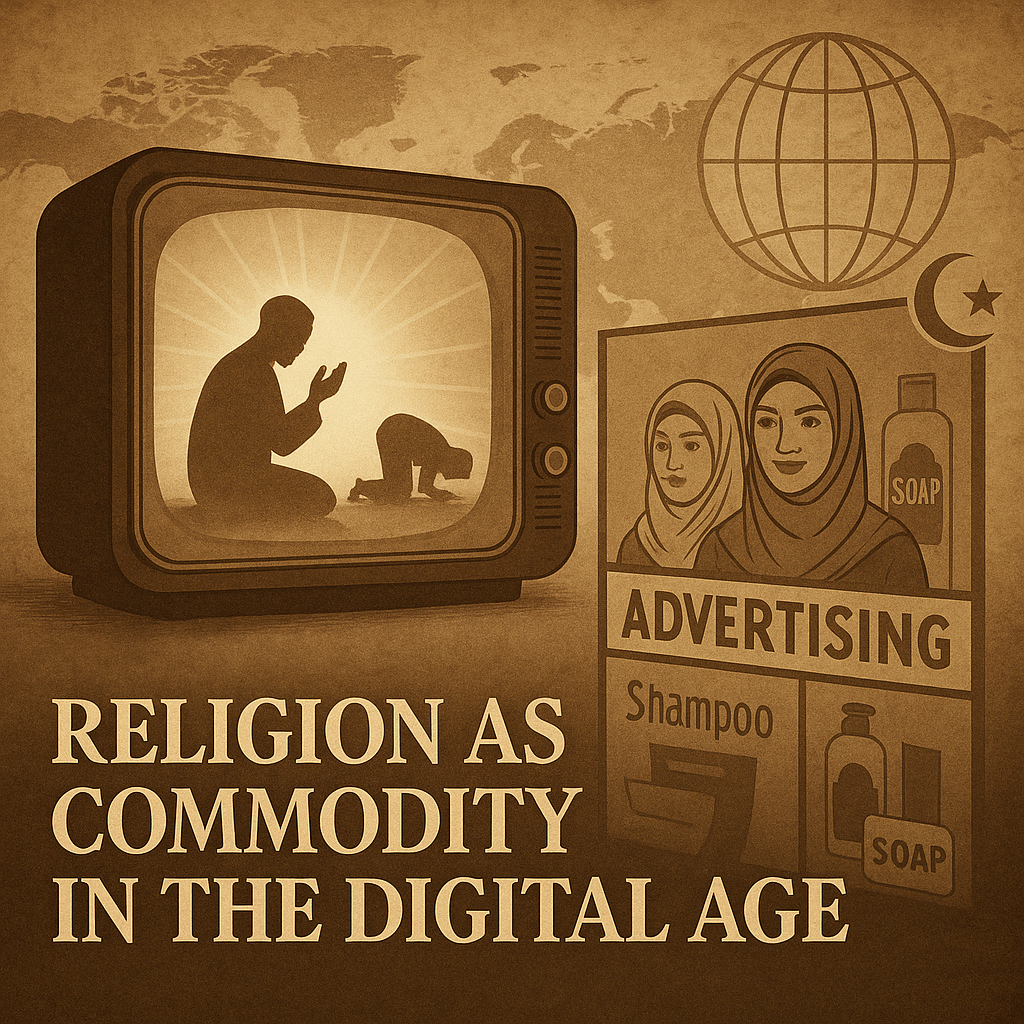

During the month of Ramadan, Indonesian media undergoes a dramatic transformation. Television screens become saturated with religious programming, advertisements suddenly adopt Islamic tones, and soap operas reframe their narratives around piety. The audience is not only entertained but also guided—at least superficially—into a spiritual atmosphere. This transformation raises questions about the commodification of religion: is faith being respected or packaged as a product?

Across digital platforms, the trend is even more visible. Social media influencers release Ramadan-themed content, from hijab tutorials to cooking shows for suhoor and iftar. The tone is spiritual, but the underlying logic remains economic. Behind every video lies sponsorship, brand collaboration, or an affiliate link. Religion is reinterpreted as an algorithm-friendly commodity.

The blurring between devotion and consumption is not accidental. Capitalism thrives by adapting itself to the rhythms of society. In Indonesia, the fasting month is one of the most lucrative seasons for advertisers. Brands understand that consumers not only fast and pray but also spend more on food, fashion, and religious goods. The “conversion” of media to Islam is therefore not simply about piety—it is about profit.

What makes Ramadan unique is that it blends sacred rituals with consumer enthusiasm. The call to prayer signals not only the time to worship but also the moment for television networks to broadcast their highest-rated shows. The suhoor hours, once quiet and intimate, are now filled with laughter from late-night comedy programs and the glitter of celebrity talk shows. Piety becomes a backdrop for consumption.

For some, this commodification might appear troubling. Religion, after all, is supposed to remain sacred, above commercial transactions. Yet others argue that it is simply a reflection of cultural demand. If people want to see religion on screen, then the market responds accordingly. In this sense, commodification is not an imposition but a negotiation between faith and modern life.

This dynamic also reflects broader social change. In a society where religion dominates identity, the market cannot ignore its power. Commercials with Islamic tones do not alienate audiences—they attract them. Thus, rather than pushing religion aside, capitalism absorbs it, reshaping it into a product.

This essay will explore how religion functions as a commodity during Ramadan, how global trends mirror the Indonesian experience, and what this means for the future of spirituality in a Planetary Civilization. At stake is not whether faith survives, but whether it thrives beyond the grip of consumer culture.

Ramadan and the Commodification of Media

Television networks in Indonesia recognize Ramadan as the golden season for revenue. PT Media Nusantara Citra Tbk (MNCN) is a prime example. By 2022, the company projected double-digit revenue growth during Ramadan and Eid, banking on increased advertising demand. Ramadan is not only a spiritual season but also an economic one, and the media industry maximizes it.

The mechanics of this commodification can be seen in the extension of prime-time broadcasting. Normally, prime time runs from 18:00 to 23:00. During Ramadan, however, prime time expands to include the suhoor hours, beginning at 01:00 and lasting until just before Fajr. This shift recognizes that audiences are awake, fasting, and looking for content. In turn, advertisers flock to these new hours, ensuring higher profits.

The programs themselves are carefully designed to blend entertainment with religious themes. Soap operas showcase Islamic characters, often with narratives of repentance or spiritual awakening. Comedians lace their routines with religious humor. Talk shows invite ustadz and celebrities alike, blurring the line between da’wah and entertainment. Ramadan becomes a theater where piety is performed for ratings.

This expansion of religious programming is not entirely cynical. For many viewers, these shows provide inspiration and comfort during a sacred month. Yet, the fact that they are also designed for profit complicates their meaning. Spirituality becomes mediated through commercial logic. Faith is not presented as an end in itself but as a means to attract advertisers.

Digital platforms mirror the same logic. YouTube creators and TikTok influencers release Ramadan series, blending cooking tutorials with reminders of fasting etiquette. Instagram feeds are filled with sponsored posts about modest fashion or halal skincare products. Even apps for prayer times and Qur’an recitation are supported by advertising. Technology ensures that religion is never free from commodification.

This commodification reveals the market’s ability to adapt. As society changes, so too does the packaging of religion. The rhythms of fasting, prayer, and devotion are now intertwined with corporate strategies and consumer culture. Ramadan, once considered a month of restraint, becomes one of the busiest periods for consumption.

In this sense, the commodification of media during Ramadan exemplifies the paradox of modern religiosity. Faith is preserved, but only by being translated into commercial form. What emerges is not the disappearance of religion but its transformation into a cultural brand.

Religion as Global Commodity

The commodification of religion is not unique to Indonesia. Around the world, religion is increasingly treated as merchandise. In the Middle East, for example, television networks compete with lavish Ramadan dramas and Qur’an recitation contests, supported by corporate sponsors. Pilgrimage packages are marketed with luxury hotels and celebrity endorsements, turning worship into an aspirational lifestyle.

In South Asia, religious festivals like Diwali or Eid al-Adha are heavily commercialized. Retailers release special collections, banks offer festive loans, and food industries push seasonal products. The sacred calendar is synchronized with economic cycles, ensuring that devotion and consumption coincide.

Western societies also display this phenomenon, though in different forms. Christmas, for instance, has long been commercialized, with Santa Claus and shopping malls overshadowing the nativity story. Similarly, yoga, rooted in Hindu spirituality, is now marketed globally as a wellness product, stripped of its original ritual depth. Religion is rebranded for secular consumption.

This raises the question of whether such commodification signifies a revival of religion or its dilution. On the one hand, religious symbols remain visible, reminding people of their spiritual roots. On the other hand, these symbols are often hollow, serving more as decorations than as pathways to transcendence.

The Indonesian case, therefore, is part of a global trend. Faith is not eliminated by modernity; instead, it is repurposed. Capitalism absorbs religion, turning it into a flexible commodity that satisfies both spiritual longing and market logic. The global nature of this trend suggests that commodification is not accidental but systemic.

What unites these examples is the fusion of devotion with consumerism. Whether through celebrity-led Umrah tours, hijab fashion shows, or religious tourism, faith becomes a lifestyle product. People consume not only food or clothing but also spirituality, packaged neatly for purchase.

This global commodification underscores the adaptability of religion. Far from vanishing, faith finds new forms of expression. The challenge is to ensure that these expressions do not trivialize or exploit the sacred.

The Market for Islamic Symbols

One of the clearest signs of commodification is the marketing of Islamic symbols. Advertising in Indonesia has undergone a striking transformation. Where commercials once relied on glamour and sensuality, they now embrace modesty and piety. The hijab has become not only a marker of identity but also a powerful marketing tool.

Shampoo commercials now feature actresses in hijabs, suggesting that beauty and faith can coexist in consumer products. Bath soap ads depict wholesome Muslim families, complete with mothers in headscarves and fathers in traditional attire. Even foreign brands adapt to the local context, renaming characters “Ahmad” or “Aisha” when entering the Indonesian market.

This adaptation reflects consumer demand. People trust products that resonate with their identity, and companies recognize that aligning with Islamic symbols guarantees broader acceptance. What was once considered niche is now mainstream, illustrating the commercial power of religious imagery.

The shift also reflects cultural transformation. Wearing a hijab in public media, once stigmatized, is now celebrated. Religious attire has moved from being a private choice to a commercial asset. Fashion brands release entire collections around Islamic dress, making modesty a form of trendsetting.

Yet, this trend is not free from criticism. Some argue that using religious symbols for marketing trivializes their spiritual meaning. Faith becomes a costume, stripped of depth and reduced to aesthetics. Others see it as empowering, allowing Muslims to integrate faith with modern consumer life.

Ultimately, the market for Islamic symbols demonstrates the dual nature of commodification. It affirms identity but also risks hollowing it out. The hijab becomes both a sacred practice and a billboard. Faith is respected, but only as long as it sells.

This paradox lies at the heart of religion in the marketplace. The symbols are preserved, but their meaning is negotiated through commerce. Whether this strengthens or weakens religion depends on how believers interpret and reclaim these symbols in daily life.

Lessons from Global Religious Economies

Globally, religion has long played a role in economic life. Amy Chua and Jed Rubenfeld, in The Triple Package (2014), argue that certain cultural and religious groups dominate business sectors because of shared values, discipline, and community networks. Religion provides not only rituals but also a mindset of resilience and ambition.

This is echoed in Boye Lafayette de Mente’s The Korean Mind (2012), which describes how Confucian ethics underpin Korean business practices. Honor, discipline, and respect for hierarchy are deeply ingrained, allowing Korea to thrive economically while retaining cultural identity. Religion here is not ritual but ethos—a force shaping work and enterprise.

Japan offers another example. Outwardly, it is highly secular, with Western cultural influence dominating. Yet spirituality persists beneath the surface. Temples remain active, rituals are observed, and festivals continue to attract thousands. Religion here functions not as doctrine but as cultural rhythm, guiding social behavior and business ethics.

These examples demonstrate that commodification does not necessarily destroy religion. Instead, it transforms how faith operates in society. Rather than being confined to rituals, religion seeps into economic practices, providing moral frameworks and motivation.

For Indonesia, this global perspective is important. The commodification of Ramadan does not mean that faith is disappearing. Instead, it signals how religion adapts to modernity. Like Korea and Japan, Indonesia negotiates the tension between tradition and capitalism.

However, there is a crucial difference. In Korea or Japan, spirituality often operates invisibly, beneath secular life. In Indonesia, religion is visibly marketed, openly displayed in advertisements and media. This visibility ensures that faith remains central, but also vulnerable to exploitation.

Thus, global lessons remind us that commodification is not inherently negative. It can empower communities, provide identity, and fuel ambition. The challenge is to balance commercial use with spiritual depth.

Post-Modernism and the Return of Religion

The Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor, in A Secular Age (2007), challenges the notion that modernity eliminates religion. Instead, he argues that faith reappears in new forms, often mediated by culture and commerce. Religion, once considered embarrassing or old-fashioned, finds renewed legitimacy in the public sphere.

In Indonesia, this is evident in the normalization of hijab on television. Where once actresses wearing hijab were sidelined, today they are celebrated. Religious identity, once hidden, becomes a badge of pride. This shift reflects not only personal conviction but also commercial opportunity. Networks recognize the appeal of piety and capitalize on it.

This post-modern return of religion is paradoxical. Faith re-enters society, but often as image rather than substance. Religious symbols are consumed, admired, and imitated, yet not always accompanied by deeper conviction. Religion survives, but as spectacle.

Still, this spectacle matters. By making religion visible, commodification keeps faith present in daily life. Even if mediated through commerce, the symbols remind society of its spiritual roots. They spark conversations about piety, modesty, and morality, even within commercial spaces.

The post-modern condition thus creates both opportunity and risk. Religion becomes more accessible, reaching wider audiences through television, advertising, and fashion. Yet it also risks trivialization, where wearing a hijab or joining an Umrah tour is more about lifestyle than belief.

For believers, the challenge is to navigate this tension. How can one embrace modern expressions of faith without losing its essence? How can religion remain sacred in a world where it is constantly marketed? These are the questions that define the post-modern religious landscape.

Taylor’s insights remind us that religion is not disappearing but transforming. Its new forms may appear shallow, but they also provide entry points for deeper engagement. The task is to reclaim meaning beneath the spectacle.

Between Individual Piety and Corporate Capitalism

In contemporary Indonesia, the paradox of faith is evident. Executives drive luxury cars while listening to Qur’anic recitations on their smartphones. Families host iftar feasts in apartments while rarely attending mosques. Corporations that do not brand themselves Islamic still donate zakat or CSR funds during Ramadan. Piety coexists with privilege, and religion functions in unexpected ways.

This dual role of religion—as individual devotion and corporate strategy—illustrates its adaptability. For believers, faith provides comfort, ritual, and identity. For businesses, it provides legitimacy, trust, and access to consumers. Religion thus serves both the soul and the market.

The result is a hybrid spirituality. A cosmopolitan professional may attend Tahajjud prayers at night while working for a capitalist company by day. A celebrity may wear hijab in advertisements while living a lifestyle that seems secular. Religion here is not erased but negotiated, woven into the fabric of modern life.

This hybrid form reflects the flexibility of faith. Rather than retreating from modernity, religion adapts, finding space within capitalism. It becomes a resource not only for salvation but also for branding. Piety is personal, yet also marketable.

Critics argue that this reduces faith to superficiality. Rituals become performances, charities become publicity, and hijab becomes fashion. Yet others argue that this visibility ensures that religion remains relevant. Even if commodified, it continues to inspire, reminding society of moral values.

The tension between authenticity and commodification cannot be ignored. Religion risks losing depth when used for profit, but it also risks irrelevance if it withdraws entirely. The balance lies in reclaiming faith’s spiritual essence while allowing it to engage with modern realities.

In this sense, religion’s role in corporate capitalism is neither entirely good nor entirely bad. It is a reflection of modern complexity, where sacredness and commerce intertwine.

|

| Source: (Don Iannone, 2021). |

The Limits of Commodification in Planetary Civilization

Looking forward, the commodification of religion may represent only a transitional phase. Don Iannone (2021) suggests that in the coming Planetary Civilization, spirituality will remain central to human life, even as technology reshapes society. Commodification will eventually give way to a deeper search for authenticity.

Artificial Intelligence, no matter how advanced, cannot replicate spiritual satisfaction. Algorithms can recommend Qur’anic recitations or simulate religious discussions, but they cannot replicate the experience of prayer or the emotional resonance of being in a sacred space. This limitation ensures that religion retains unique value.

Take, for example, the call to prayer from Mecca. Millions may watch it on YouTube, but the experience cannot compare to standing in the Haram, surrounded by worshippers. Spiritual encounters demand physical presence and authenticity, which technology cannot substitute. This ensures that religion will survive commodification.

The danger, however, lies in allowing commodification to dominate. If religion is reduced to advertising campaigns and lifestyle products, it risks being hollowed out. Followers may eventually reject such artificial expressions, seeking instead authentic spiritual experiences.

Planetary Civilization will likely test religion’s resilience. On the one hand, faith will be marketed and digitized. On the other, it will inspire people to resist artificiality, seeking real connection with the divine. Commodification may dominate temporarily, but authenticity will endure.

This tension highlights the need for balance. Religion cannot withdraw from modern life, but it must also guard against being consumed entirely by capitalism. Its survival depends on its ability to provide meaning beyond material gain.

Ultimately, spirituality ensures that humanity does not become fully mechanized. Even in an age dominated by AI and global networks, the sacred will remain indispensable.

Conclusion: Faith Beyond Commodification

The commodification of religion is both a sign of its strength and its vulnerability. In Indonesia, Ramadan exemplifies how faith can be turned into profit, shaping television, advertising, and digital platforms. Globally, similar trends show how religion adapts to capitalism, from Christmas sales in the West to Umrah tours in the Middle East.

This does not mean that religion is disappearing. On the contrary, it remains central, visible, and influential. Yet its visibility comes at a cost: faith risks being reduced to image, symbol, and product. The sacred is preserved, but often through the logic of the market.

The challenge is not to reject commodification outright but to navigate it. Believers must reclaim depth beneath the spectacle, ensuring that symbols remain meaningful. Businesses must recognize the ethical limits of marketing faith, avoiding exploitation. Society must learn to balance piety and profit.

The global context reminds us that commodification is not unique. Religion has always adapted to social and economic change. The key question is whether it emerges from these adaptations strengthened or hollowed out.

In the transition to a Planetary Civilization, authenticity will matter more than ever. Technology may reshape rituals, but it cannot replace spirituality. Faith endures because it provides what commerce cannot: meaning, transcendence, and connection to the divine.

Therefore, while religion may temporarily function as a commodity, its ultimate role lies beyond consumerism. It will remain central in human life, guiding individuals and societies toward values that capitalism alone cannot provide.

Leave a Reply